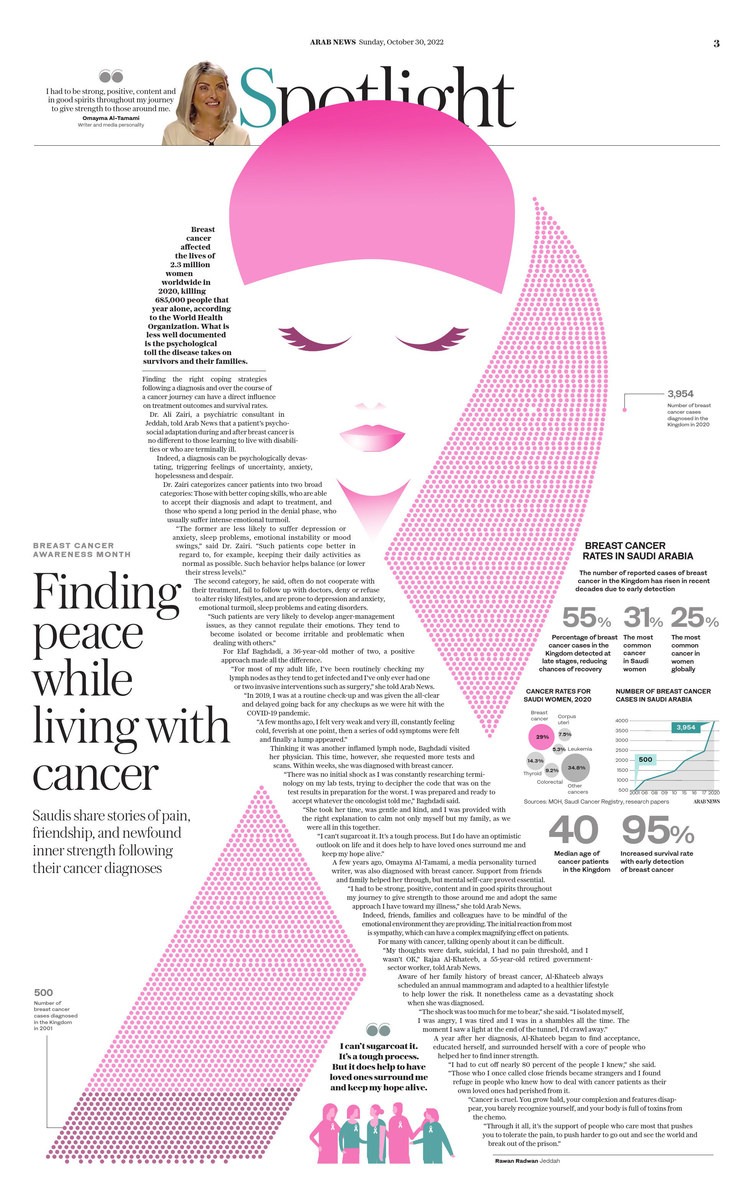

JEDDAH: Breast cancer affected the lives of 2.3 million women worldwide in 2020, killing 685,000 people that year alone, according to the World Health Organization. What is less well documented is the psychological toll the disease takes on survivors and their families.

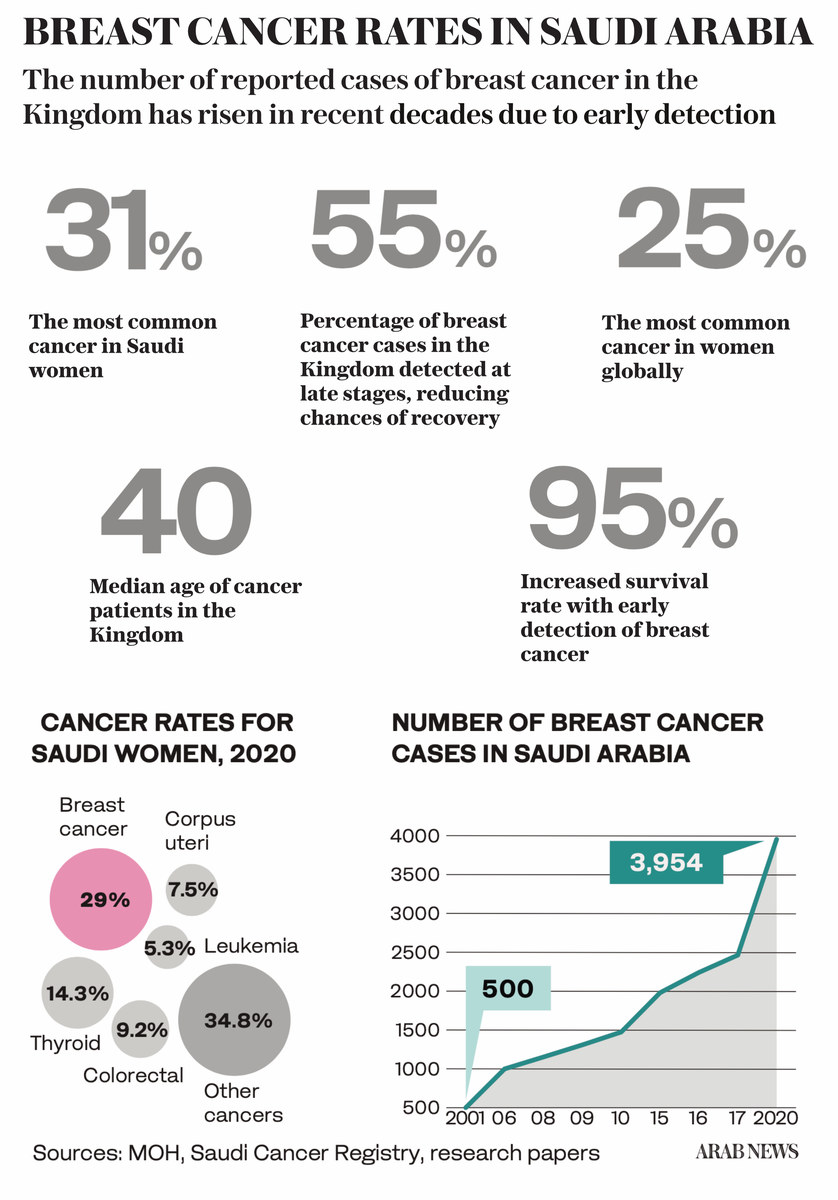

In Saudi Arabia, breast cancer accounts for 31 percent of all cancer diagnoses, making it the most common form of the disease. Although mammography was introduced to the Kingdom in 2002, 55 percent of cases are detected at a late stage, reducing chances of recovery.

Several studies indicate that 20-30 percent of women diagnosed, treated and declared free of local or regional invasive breast cancer will suffer a recurrence. There is therefore a constant fear among survivors that their cancer could come back.

Finding the right coping strategies following a diagnosis and over the course of a cancer journey can have a direct influence on treatment outcomes and survival rates.

Cancer significantly impacts all spheres of life, provoking a variety of emotional and behavioral responses, which means there is no “one size fits all” approach to help patients cope.

Dr. Ali Zairi, a psychiatric consultant in Jeddah, told Arab News that a patient’s psycho-social adaptation during and after breast cancer is no different to those learning to live with disabilities or who are terminally ill.

Indeed, a diagnosis can be psychologically devastating, triggering feelings of uncertainty, anxiety, hopelessness and despair. Psychological distress, including depression, is common.

Dr. Zairi categorizes cancer patients into two broad categories: Those with better coping skills, who are able to accept their diagnosis and adapt to treatment, and those who spend a long period in the denial phase, who usually suffer intense emotional turmoil.

Shutterstock image

“The former are less likely to suffer depression or anxiety, sleep problems, emotional lability or mood problems,” said Dr. Zairi. “Such patients cope better in regard to, for example, keeping their daily activities as normal as possible. Such behavior helps balance their stresses or buffer their stresses to the lowest possible degree.”

The latter, he said, often do not cooperate with their treatment, fail to follow up with doctors, deny or refuse to stop risky lifestyles, and are prone to depression and anxiety, emotional turmoil, sleep problems and eating disorders.

“Such patients are very likely to develop anger mismanagement as they cannot regulate their emotions. They tend to be isolated or become irritable and problematic when dealing with others.”

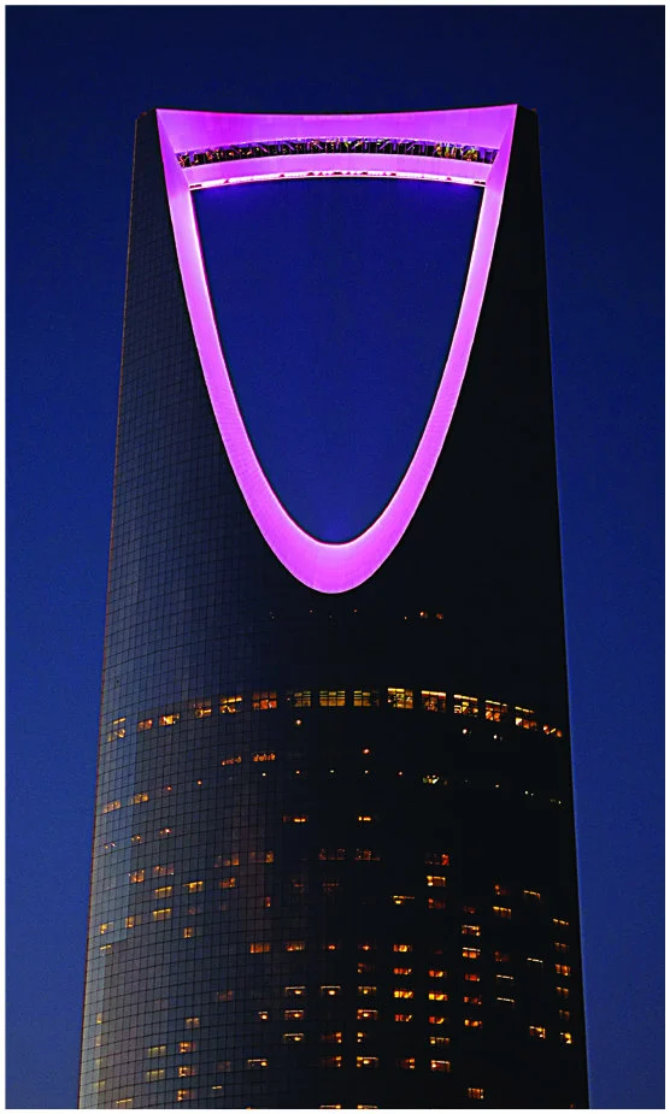

Every year, Riyadh's iconic Kingdom Tower goes pink to help promote breast cancer awareness. (AN file photo)

For Elaf Baghdadi, a 36-year-old mother of two, it never occurred to her that her history with lymphadenitis, an infection of one or more of the lymph nodes, could lead to a more severe problem.

“For most of my adult life, I’ve been routinely checking my lymph nodes as they tend to get infected and I’ve only ever had one or two invasive interventions such as surgery,” she told Arab News.

“In 2019, I was at a routine check-up and was given the all-clear and delayed going back for any checkups as we were hit with the COVID-19 pandemic.

“A few months ago, I felt very weak and very ill, constantly feeling cold, feverish at one point, then a series of odd symptoms were felt and finally a lump appeared and it was odd enough to raise my concern but only by a fraction.”

Thinking it was another inflamed lymph node, Baghdadi visited her physician during the summer. This time, however, she requested more tests and scans, “to make sure.” Within weeks, she was diagnosed with breast cancer.

“There was no initial shock as I was constantly researching terminology on my lab tests, trying to decipher the code that was on the test results in preparation for the worst. I was prepared and ready to accept whatever the oncologist told me.

“She took her time, was gentle and kind, and I was provided with the right explanation to calm not only myself but my family as we were all in this together.”

A diagnosis can be psychologically devastating, says psychiatrist Ali Zairi. (Shutterstock image)

It was thanks to her calm demeanor that Baghdadi could face the challenges of diagnosis, biopsy, surgeries and treatment.

“The first time I broke down was right after my mastectomy. It was the second day, I had the Qur’an playing next to me, and one verse broke my tears free,” she said.

“I knew that it was going to be difficult and I was ready, but you can never be ready enough. One short verse reminded me of how weak as humans we are and that played with my psyche.

“I can’t sugarcoat it. It’s a tough process. And in my case, one thing led to the next. I’m due to start my chemotherapy by the end of the month. But I do have an optimistic outlook on life and it does help to have loved ones surround me and keep my hope alive,” she said.

A few years ago, Omayma Al-Tamami, a media personality turned writer, also began a battle with breast cancer, which had been picked up late owing to a misdiagnosis. Support from friends and family helped her through, but mental self-care proved essential.

“I had to be strong, positive, content and in good spirits throughout my journey to give strength to those around me and adopt the same approach I have toward my illness,” she told Arab News.

Indeed, friends, families and colleagues have to be mindful of the emotional environment they are providing cancer patients. The initial reaction for most is sympathy, which can have a complex magnifying effect on patients.

Support of people who care most can strengthen cancer patients into tolerating the pain, says one survivor. (Shutterstock image)

Al-Tamami says cancer patients do not need pity. Instead they need honest and open conversation to address the disease head on.

For some, however, such open conversation is easier said than done.

“My thoughts were dark, suicidal, I had no pain threshold, and I wasn’t OK,” Rajaa Al-Khateeb, a 55-year-old retired government-sector worker, told Arab News.

Aware of her family history of breast cancer, Al-Khateeb always scheduled an annual mammogram and adapted to a healthier lifestyle to help lower the risk. It nonetheless came as a devastating shock when she was diagnosed.

“The shock was too much for me to bear,” she said. “I isolated myself, I was angry, I was tired and I was in a shambles all the time. The moment I saw a light at the end of the tunnel, I’d crawl away.”

A year after her diagnosis, Al-Khateeb began to find acceptance, educated herself, and surrounded herself with a core of people who helped her to find inner strength.

“I had to cut off nearly 80 percent of the people I knew,” she said. “Those who I once called close friends became strangers and I found refuge in people who knew how to deal with cancer patients as their own loved ones had perished from it.

“Cancer is cruel. You grow bald, your complexion and features disappear, you barely recognize yourself, and your body is full of toxins from the chemo.

“Through it all, it’s the support of people who care most that pushes you to tolerate the pain, to push harder to go out and see the world and break out of the prison.”